Where was the first bridge of the Battle of Monte Cassino?

A mission to locate a wartime bridge over the River Garigliano - in which I find deeper meaning in my father's final words

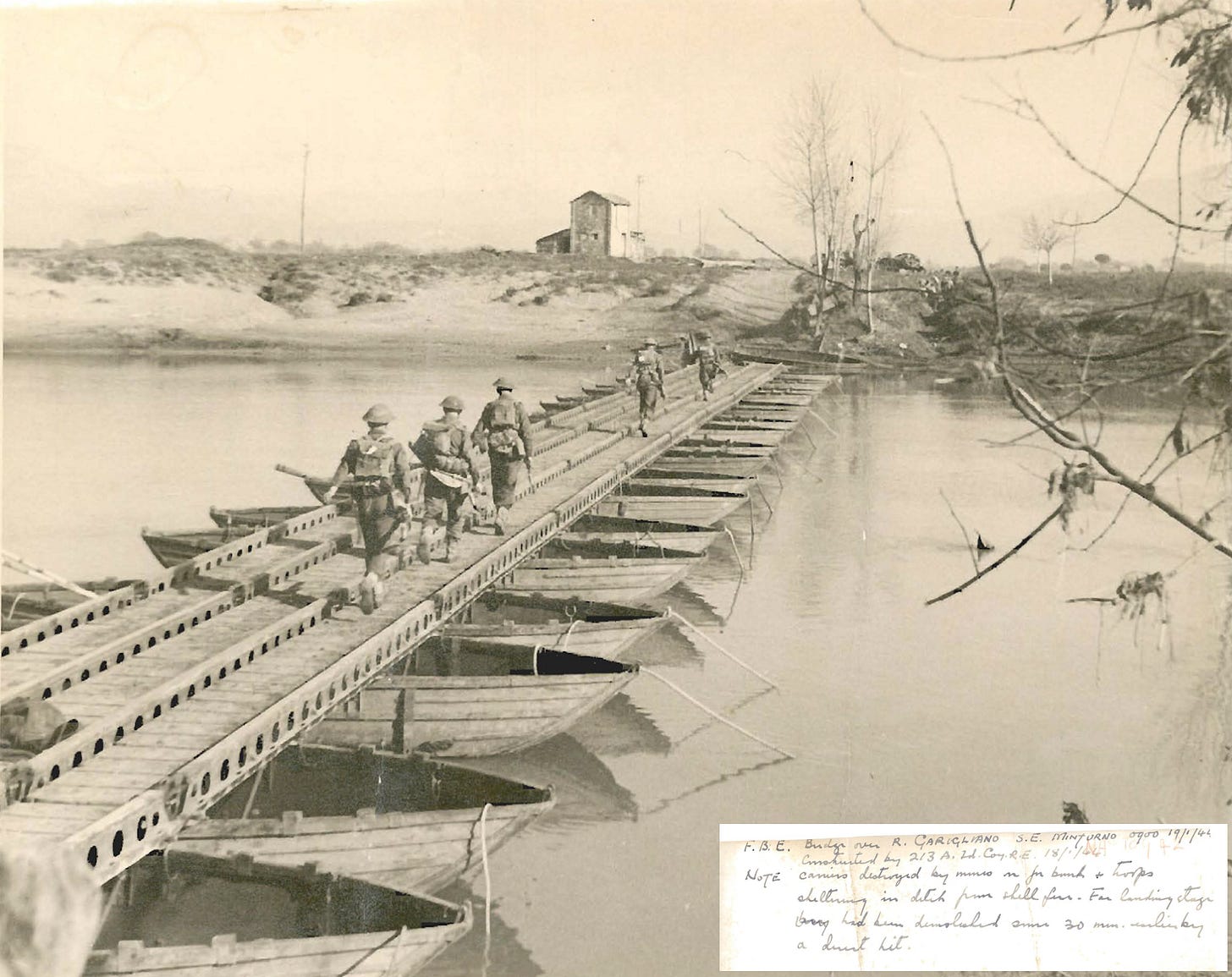

On the night of 18 January 1944, 80 years ago, men of the British 213 Army Field Company Royal Engineers constructed a pontoon bridge across the River Garigliano to the south east of Minturno in Italy, on the border of the provinces of Lazio and Campania.

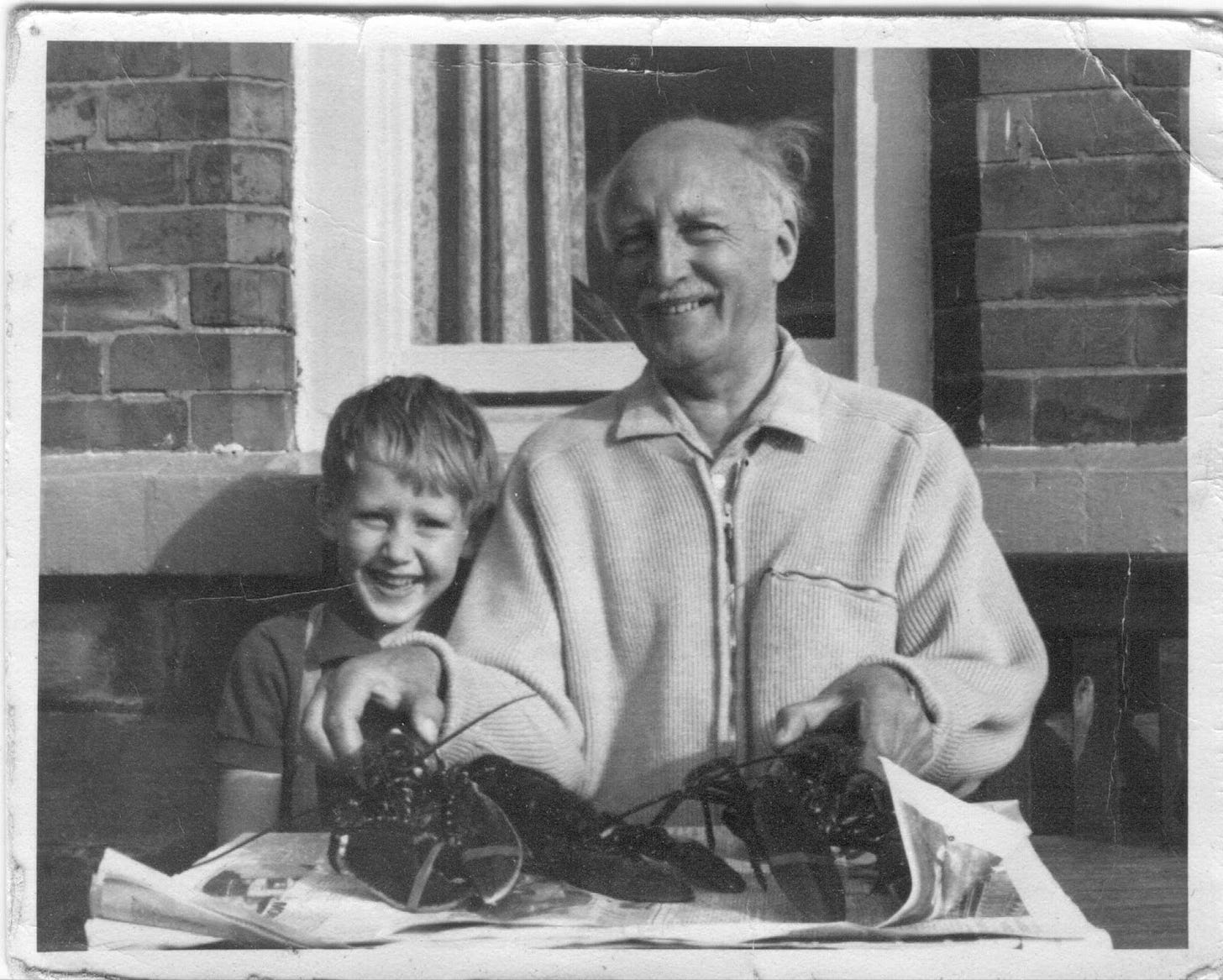

Since I was a small boy in the 1960s, and probably long before, a framed picture of that bridge hung on the wall of our family home. I remember staring at the photo as my dad (who died in 1970 when I was 9) described the difficulty of building it under enemy fire and how he had received the Military Cross (a British Armed Forces medal for ‘exemplary gallantry’) for its construction.

Today, of course, there will be no obvious trace of such a bridge - it will have likely been quickly superseded and disassembled after the war or even before it ended. So where precisely was it?

On 17-19 January this year, to commemorate its 80th anniversary and the work of 213 Company, I went with my wife Kirsten to the Garigliano, staying in the nearby hill town of Minturno, on a mission to answer this question.

The context

The context for the bridge was a WW2 battle that came to be known as The Battle of Monte Cassino - and specifically the first day of that battle. The goal of the Allied forces was to liberate Rome. The goal of their German opponents was to block the Allies’ progress at the Gustav Line – a series of fortified positions across Italy from coast to coast where the mountainous terrain gave the Germans significant defensive advantages against the Allies’ otherwise much superior ground forces, naval support, and air power. The battle would become a brutal four-month struggle, leaving 55,000 Allied and 20,000 German dead or wounded, and a most appalling civilian impact, before an Allied victory was secured.

The Battle of Monte Cassino began with an assault by the British X Corp across the lower Garigliano on 17 January 1944 - men and equipment were transported initially in small boats, then rope drawn ferries, but to transport heavy equipment and higher volumes of men and materiel, bridges were required.

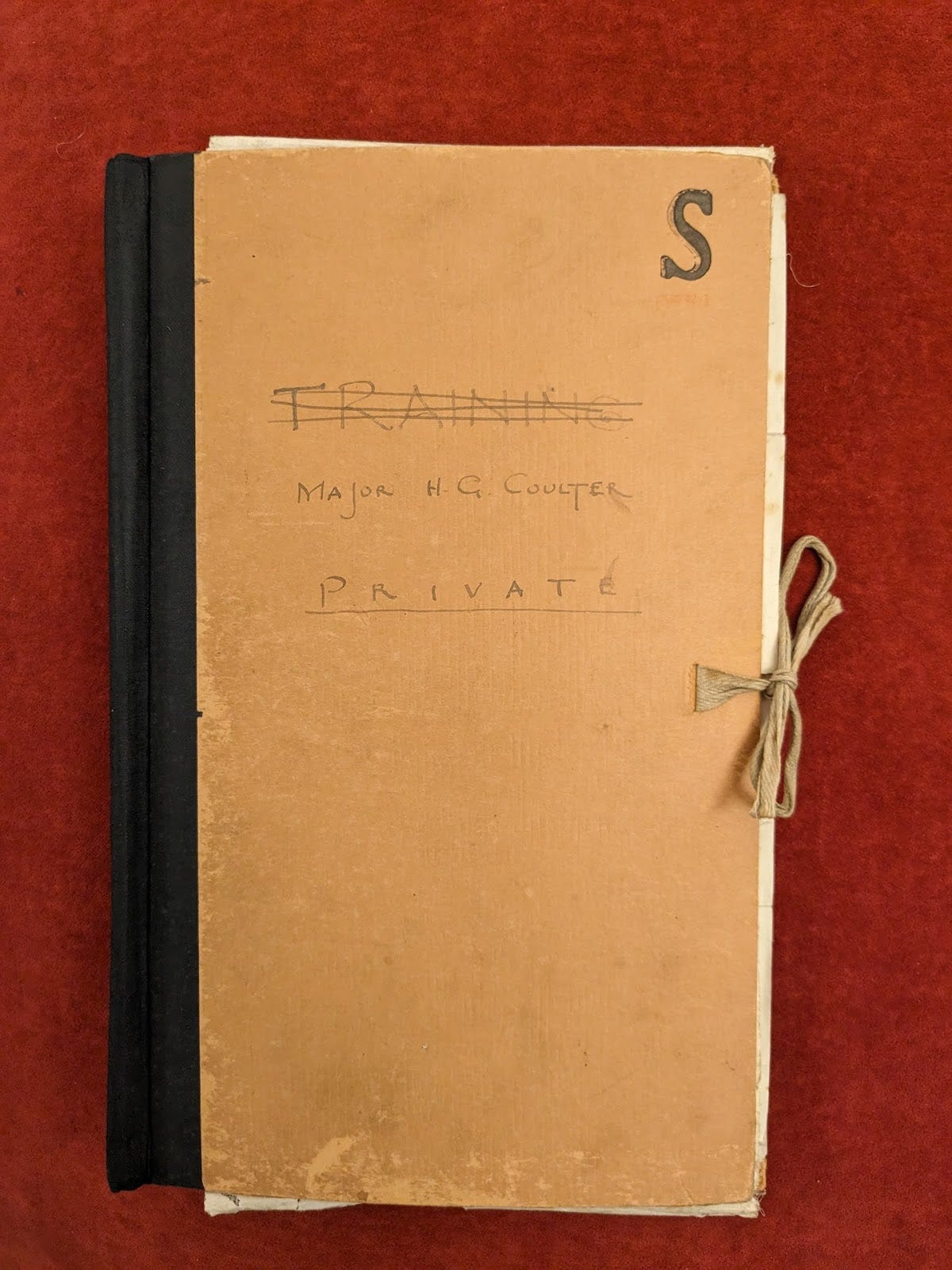

The bridge in question was the first over the Garigliano-Rapido river system, a natural barrier supporting the Gustav Line. The officer commanding 213 Company, an engineering unit of 240 men, 7 officers, and 31 vehicles of various types, was Major H.G. Coulter (HGC), 36 - known always as George to friends.

In civilian life he was an architect and, having joined the British Army Supplementary Reserve (a part-time force of ‘skilled tradespeople’) in 1935, was immediately called up in 1939 at the outbreak of war. As a junior officer in 213 Company, he had taken part in the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in Northern France in 1939/40 and experienced its retreat back to Britain, during which a number of men of the Company lost their lives and many were captured, including its commanding officer. Promoted, he was then in charge of a reformed 213 Company and he spent two years training with his men (he said ‘training is everything’) in Ripon, Yorkshire, elsewhere in England, and in Scotland. And in that time, he also met and married Elaine Jackson of Leeds and had a son, Christopher. He took part in the invasion of Sicily in July/August 1943, arriving in Italy proper on 9 September 1943, the first day of amphibious landings at Salerno as part of ‘Operation Avalanche’ (sometimes called a ‘dress rehearsal for D-Day’ - the vast Allied re-invasion of Normandy). Today it is a leisurely two hour Autostrada journey from the site of the Salerno landings south of the Amalfi peninsula to the Garigliano river north of Naples. In 1943, it took the Allies over four months, as the German Army made a fighting retreat.

So on 17 January, after two days in the Salerno area and visiting the landing beaches and the graves of two men of 213 Company who had lost their lives there, Kirsten and I drove north, following their approximate route, via the town of Grazzanise on the River Volturno (where 213 Company had repaired the bridge damaged by crossing of a Sherman tank), to spend two days searching for the site of the this long-gone Garigliano bridge.

The clues - pre-visit preparation

Photo caption

HGC’s photo caption above “S.E. Minturno” indicates the bridge was somewhere between, say, South-South-East and East-South-East of the boundaries of Minturno, which would include the village of Tufo. This narrows the search area down to a section of the river indicated on the modern map below.

Photographs

It was very fortunate to find multiple contemporaneous photographs of the bridge (some in colour) on the Imperial War Museum (IWM) website. This included the very picture that Dad had kept and framed.

I have a memory of my dad pointing at the farm building on the far bank of the river, explaining that there had been Germans there, that they were shooting at his side and they had to be dealt with. True or false memory? I was 7, 8, or 9 and this was 1967-69. I have certainly always assumed that the pictures are looking in the direction of attack - towards the enemy and generally in a northerly direction.

Before the trip to Italy, I tried with Google Street View and Satellite View to locate anything from the pictures - the building, the exact mountain shape, the sandy coloured far bank, the ditch, and the road or track - but was entirely unsuccessful. Street View is limited to serviceable roads and many vantage points are blocked by trees or banks or just the weather of the day. There was no sign in Satellite View of the sandy coloured far bank anywhere in the search area of the river

An onsite comparison with the scenery, especially the mountains (as the riverside and buildings have likely been a much developed or changed), should be able to reveal the location. The background mountain ranges are a fingerprint and only at the exact location of the bridge will the ranges of different distances form the outline seen in the photograph.

HGC’s report on the Garigliano Crossing, dated 2 February 1944

Sometime around 1995, my mother presented me with an old folder of documents. She had been clearing out the house and said: “You’ve been asking me for anything about your dad - here are some things he kept - I’m afraid it is all I can find”.

Amongst them was his typed report entitled “213th Army Field Company R.E., Crossing of River Garigliano” and dated 2 February 1944, two weeks after the event. It is quite detailed, 3 pages of 8x10 inch paper, but it does not reveal the coordinates of the bridge. Perhaps he saw no need or, quite likely, a standard security measure. Nevertheless, there are multiple clues in the text and these are laid out in the table that follows.

Accounts of opening stages of Battle of Monte Cassino by historians

Matthew Parker shows a map of the Garigliano Crossing in his 2003 book Monte Cassino, indicating two approximate search sites - downstream (west) of the destroyed Bourbon bridge (17th brigade) and upstream (east) of it (13 & 15th brigades).

More clues - onsite at the River Garigliano

Search - Day 1 (18 January)

Last week on 18 January, Kirsten and I searched the two areas on the map above hoping to find the spot.

But first, we went to a small ceremony in Tufo where, standing by the village war memorial for Italian war dead in a square overlooking the Garigliano valley and in the winter sun, the mayor gave a speech acknowledging the sacrifice of the fallen. Afterward we asked a few of the older people - some of whom may have been very young at the time of the crossing - where the picture of the bridge might have been taken. None were definite, but waived generally in the direction of the area upstream of the Bourbon bridge.

Late morning we went up and down the downstream area - this was not promising. River banks were not high enough, no signs of the sandy colour ground, and the background, although mountainous, did not match well to the photographs.

In the afternoon, we went upstream along Route 7. There is a continuous bank preventing views of the river from the road itself, but there are four or more farmer’s access points that go up and over the bank into tracks through the fields. We stopped at several of these and walked in two or three places to and along the river. These viewings were more tantalising - we did not see an exact mountain match - and the haze was obstructing some of the scenery as the day progressed. But it looked promising, especially at our first stopping point moving from east to west along the road. We also saw patches of exposed sandy-colour far bank in spots, though nothing like the extended bare area in the 1944 photography.

Search - Day 2 (19 January)

We were fortunate to have been put in contact by Giusy, our apartment host in Minturno, with two local historians - Giuseppe Caucci and Mirco Mendico. Giuseppe, President of the Gustav Line Garigliano Front Association, has been fascinated by the military history in the area since he found a piece of shrapnel while on vacation aged 8. He has built a museum of artefacts and stories in Castelforte. Mirco is similarly passionate about local history and represents the historical and memory activities for Minturno - we had been introduced at the ceremony in Tufo the previous day.

We visited the downstream area from the old Bourbon Route 7 bridge where Giuseppe discussed the possibilities there. He then produced, from a thick folder of collected information, aerial reconnaissance photography of the river area from September 1943. This was superb - a brand new, highly relevant set of clues. And was likely the same ‘late summer’ reconnaissance that HGC refers to as having studied and found so useful for planning the bridge in his 2 Feb 1944 report.

Kirsten and I had approached a number of local inhabitants the previous day to ask about the potential site - they all said things like ‘we don’t know - you see much has changed since then’. However, the aerial photography shows surprisingly little has changed that is of relevance to our search. Importantly, the course of the river is identical - even where the river meanders in the upstream area. The roads, major or minor, and the railway around the river and even most of the farmer’s track, and many of the field layouts, are in the same position as they were 80 years ago. Notably there was a road either side of the river in the downstream area (as there is today) - these are absent from the bridge photograph and HGC’s description of the bridge site. So I think the downstream area can be excluded from the search for that reason.

Giuseppe also recommended using Google Earth to match the mountain scenery - a good tip, as we will see later.

We went to the archaeological area of Roman Minturnae, located on Via Appia just beyond the Bourbon bridge. British officers - and quite possibly HGC - had stationed themselves there after the crossing, taking advantage of shelter under the well-constructed Roman amphitheatre.

We then went to the upstream area where Giuseppe and Mirco surveyed the view looking north and north east from the top of one of the farmer’s crossing points across the bank shielding Route 7 from the river.

Next we visited the museum in Castelforte. Half-way through what was a most fascinating tour, Giuseppe, Mirco and colleagues exclaimed ‘we have found something, the answer - in a video!’.

The movie pans across the bridge scene briefly as a vehicle crosses it. The scene was recognizable to the local team. Nevertheless the precise coordinates of the bridge remained unknown to us. Pressed for time, Giuseppe left for his day-job in Naples, while we and Mirco left for an interview scheduled with local journalist, Antonio Lepone, at a cafe on the Via Appia in Minturno.

Afterward we visited the Minturno War Cemetery to pay respects to the circa 2,000 British and Commonwealth soldiers buried there. There are none from 213 Company amongst them. Finally, we flew home to Cambridge. It had been an incredible two days and we felt close to solving the mystery conclusively.

Back home - and the solution to the mystery

I asked the family WhatsApp group for help with the geolocation of the photo. Younger, tech-savvier minds? Might work?

It took just 16 minutes for one child, Dr Lucia Coulter, 29, to make the critical discovery using Google Street View.

Later that afternoon, using Google Earth as recommended by Giuseppe, we made the exact match. The mystery was solved. I must return soon to visit the exact site from either side.

Could I have located the site earlier?

Knowing the bridge site and seeing how perfect it is, how it fits the clues so brilliantly – I have to ask myself, could I have found it earlier? Possibly not, but I did miss clues and, perhaps, I was too wedded to certain ideas or assumptions.

For instance, it turns out the bridge was facing north-east. I had imagined it pointed north or north-west in the general direction of troop movement on 17-19 January as the allies pushed to occupy Tufo and Minturno. An unnecessary imagination.

The mention of a ‘flood wall’ in HGCs report - I had no idea what this was and could have investigated. Now I know - next time that I see a 2m high bank between a river and a road, I will know why it is there.

And his mention of the river bend - I discounted the possibility that this meant a big meandering bend - I imagined bridging a longish, straight-ish section of the river - certainly not one that could leave your back exposed to enemy territory. But that is not the imaginings of a military engineer.

Bridge built, job done?

No.

Lt-Colonel K H Osborne, HGC’s immediate commanding officer, wrote a letter of appreciation to HGC on 26 Feb 1944. Using delightful British understatement, he congratulates all ranks on their inspiring effort to carry on with the job “despite heavy enemy interference” and notes that 213 Company contributed to a large extent to the successful maintenance of the forward Infantry “for many trying days”. Rather in the style of “Heavy rain interfered with our cricket match - it was a most trying afternoon”.

Brigadier B T Godfrey-Faussett, Chief Engineer of X Corp, gives more revealing detail in the citation for HGC’s Military Cross:

“For the attack across the R.Garigliano on 17 Jan Maj. Coulter was responsible for the construction of the first bridge to be put across the river behind the assaulting infantry. Due to the open nature of the Garigliano valley the bridge was in full view of the enemy O.Ps. [observation posts] and subject to frequent and accurate artillery fire. Major Coulter’s Fd. Coy. maintained the bridge for two months, during which period it was shelled almost daily, was three times partially destroyed and rebuilt.

To the personal example of cool courage and determination set by Maj. Coulter to his unit throughout this period when repairs to the bridge, which was an accurately registered target, had repeatedly to be carried out while shelling was still going on in order to prevent boats which been holed by splinters from sinking, was largely due to the continued existence over so long a period of this very important bridge.”

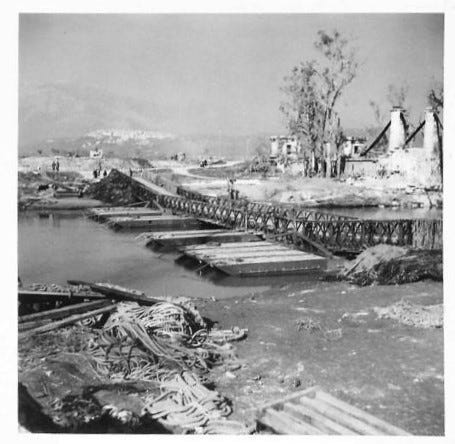

Amonst HGC’s papers is a technical drawing, in his handwriting, of a second heavier Garigliano bridge - a Class 30 Bailey. It closely resembles that photographed on 21 January 1944, located adjacent to the destroyed Bourbon bridge on Route 7, apart from two extra supporting rafts in the centre. Was 213 Company responsible for this bridge also? Perhaps HGC, a skilled draughtsman from his civilian profession, lent a hand to another unit? Or was it an upgrade for 213’s F.B.E. bridge? It is unclear.

Postscript: one step deeper

I am so pleased to have made the effort to be in situ for the 80th anniversary of a critical event in Dad’s life and to gain a better understanding of the meaning of that picture on the wall. Did I close a loop? If not then, when would I have. And if I am honest, surely I was motivated to go there to try in some strange way to be close to the father I lost at a young age.

Here are two questions I have been asked from time to time and feel it is important that I try to answer them.

He must have been very brave? A hero?

Actually, I think not especially or exceptionally. Apart from a few personal memories, I am relying on other people to describe his personality: gentle, kindly, 'genuinely nervous', cautious, risk-averse (for which there is even genetic evidence), unassuming, modest. He had a slow and considered decision-making style. He was hard-working and possessed 'sincerity of purpose'. He ‘invariably wore a charming smile’, was sociable, 'good company' and ‘knew the art of understanding people’. He enjoyed good food and wine. He had a marvelous memory and was an engaging story-teller, stories that often contained a profound moral.

His cousin Edith, two years his junior, knew him longer than anyone - they had grown up in neighbouring 'two-up, two-down' terraced houses in a non-salubrious part of Kent between the Thames estuary and the local quarries. She simply described him as 'so kind and gentle in all his ways'.

At the age of 9, during WW1 in 1916, he witnessed a German Zeppelin airship, on its way to bomb and terrorize London, shot down, flames spreading from one end to the other. He was amazed that people on the ground were cheering in merriment - he was thinking of the aviators in the cabin beneath, plunging to their fiery deaths.

Early in the war, during the retreat from Northern France, he escaped with his men through enemy lines, travelling only at night - he recalled a sense of primaeval terror while hiding in the Normandy forests under threat of machine gun, mortar, or artillery fire.

My brother Timothy recounts asking, as a small boy would, ‘Dad, did you kill any Germans?’ To which he replied that he tried not to - on one occasion in Italy there were German infantry in the next field and he retreated rather than take them on. He thought it better to ‘live to fight another day’.

No, HGC was in no way the warrior type. Perhaps more worrier. Yet despite his gentle nature, he had developed resilience, 'quiet strength' as one friend put it - or 'cool courage and determination' according to his commanding officer.

I am sure he tried to stay safe and keep his men safe - to stay out of harm's way and not to take unnecessary risks or engage in heroics - while doing a job with competence (good planning and execution) and to the best of his ability. And, as his wartime reports indicate, always looking to learn from experience and always understanding that training was a key to survival as well as effectiveness.

You must be proud of his achievement?

Well, only in that the achievement reflects an attitude and an approach to life. He trained, he prepared, he took the initiative on occasion, and the results followed - or if not, he learned. When there was no war, the same applied in his architectural work. He worked equally hard on family life, looking to equip us for good lives. The four Coulter children, we were lucky to have this father. So pride is not the best word. Gratitude, for everything he did and for the good fortune we had, is the one I would use. (He also, by the way and not withstanding his experiences in Sicily and Italy in 1943/44, had an enduring love of all things Mediterranean and classical, and passed that appreciation onto us. Brother Chris relates that he had visited Italy several times before WW2 with his parents and spoke so fondly of Italian architecture, art, culture, and food.)

It seems to me that HGC faced a big question in his life: How do the gentle, the quiet, the kindly, the nervous, and the well-meaning face off against the aggression, oppression, or adversity that comes our way? He seems to have worked out some answers, at least for his own situation.

Homecoming

HGC and the men of 213 Company returned to England that spring in preparation for the invasion of Normandy. Many more bridges were to be built before the war’s end. Their ship left Italy on 4 March, arriving home on the 16th via the Scottish port of Gourock on the Clyde estuary. Dad presented an orange (a rare commodity in Northern Europe at that time) to his now 13 month old son, Christopher. They had spent six gruelling months in Italy and two before in Sicily and may well have mused on the popular poem ‘Home Thoughts from Abroad’ written by homesick poet, Robert Browning, while in Italy a century before.

As it happens, HGC recited these very words as he drove me to school, the morning of the day he died, Saturday 31 January 1970. They are the last words I remember him saying. I only just realised the connection, that these words had a deeper meaning.

Oh my. I don’t know where to begin. You’ve found what I’ve been looking for thirty years. In my good fortune, I feel slightly lightheaded.

The bridge your father built remains a critical part of my family history. My father, an American combat engineer of World War II, spoke to me of that bridge only once. What he said frightened and fascinated me, in equal parts.

After decades of needing to locate this bridge myself – to seek the same answers about my father as you have yours – my wife and I decided recently to hire a historian in Italy to assist in locating the bridge area. With your fascinating journey beautifully chronicled, I'm entirely confident we will visit in May of 2025 the correct place on the Garigliano where pivotal military events occurred in 1944.

At the same moment your father began constructing the bridge, my father was attempting to cross the Rapido River (upper Garigliano) with his unit supporting the American 36th Infantry Division. Needless to say, it was a slaughter of breathtaking proportion. There were as many American casualties at the Rapido – more than 2,000 – as Omaha Beach on June 6 of that year.

On 5 March, 1944, my father’s unit, the 19th Combat Engineer Regiment, learned the new American 88th Infantry Division was to relieve the battered British 46th Infantry Division along the Garigliano River in the Minturno area. On 28 March, the US II Corps would relieve the British X Corps in offensive operations on the west coast of Italy. Dad’s unit would maintain roads and bridges beginning 30 March, with his company taking over the 24-hour maintenance of the bridge your father built.

On the night of 28-29 April, a dozen men – my father among them – held the bridge through an extraordinary German artillery pounding, keeping it operational at a critical juncture of the battle. On this bridge, my father’s best fried died in Dad’s arms, mortally wounded from an artillery burst. As a young boy, my father mentioned this night only once, and in shorthand terms. “I was covered in blood, and wasn’t sure if I’d been hit”, he said to me. This 24-hour effort resulted in these dozen men being awarded the Silver Star Medal for battlefield gallantry – the most decorations for any battlefield event in the 19th Engineers regimental history. I have the official citation of this if you’d like a copy. After years of research, I produced a documentary about my father’s outfit, found at YouTube when searching, “Wiped Out: Hard Luck WW2 Outfit”. This film features first-hand accounts of men who were on your father’s bridge.

My father, Clayton H. Nelson, died when I was young, too. So many veterans of the war came home, went back to work, started families, enjoyed what the post-war years could deliver, then they were gone. What remains is our undying respect for what they were able to accomplish under dreadful conditions.

Thank you, Patrick, for sharing your absolutely marvelous journey. Superb detective work! It’s wild to consider your father and mine occupied the same foxholes and trenches reserved for the soldiers maintaining the bridge. The timing of your brilliant article couldn’t be more perfect. Thank you, a million times.

Timothy Nelson

Nevada, USA

Patrick, what a fantastic post, thank you for taking the time to write it up. Very clear, great narrative and amazing photos. I was searching on the Garigliano to understand more about a commando raid that preceded the crossings, 81 tears ago tonight as it happens. But I was drawn into your story and, faced with the same problem, I would have made all the assumptions you did! I would have gone to Google Earth earlier but as I would have been looking in the wrong place, it would not have profited me. I'm delighted you found the bridge site.

Best wishes, Andrew (www.beardenwm.blogspot.com)